By David Fleet

Editor

It’s been 50 years this week that police vice squads raided an after hours drinking club or ‘blind pig’ in a mostly black Detroit neighborhood at 12th Street and Clairmount Avenue.

According to newspaper reports, the squad found 82 people inside the club, holding a party for two returning Vietnam veterans. The mostly white officers tried to arrest everyone at the club and transport the arrested patrons to jail.

When the police left the club area, a few men who were “confused and upset” because they were kicked out of the only place they had to go, lifted up the bars of a nearby clothing store and broke the windows. Following the break-ins, looting and fires spread through the northwest side of Detroit, then crossed over to the east side.

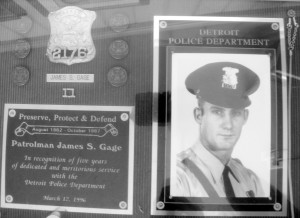

“I never fired my gun,” recalled Jim Gage, 76, now an Atlas Township resident who was a Detroit police officer in 1967. Gage’s more than 40-year police career also included stints with the Michigan State Police and Genesee County Sheriff Department. He retired in 2011.

Gage, a Bad Axe native, was 21-years-old when he joined the Detroit Police Department on Aug. 3, 1962. He was assigned to the 11th Precinct Station at Davison and Conant streets in Detroit.

“I was 26 years old the first day of the riots on July 23, 1967, it was a Sunday and I was working the day shift,” said Gage. “You could see the smoke to the west of us near the 10th Precinct on Livernois Avenue. The locals were getting really nervous, it was just a very tense time in the city. I happened to have a few days off so I left town when my shift was over and we drove to Bad Axe. I got the call to get back to Detroit right away.”

Gage and his wife were living in an apartment near 7 Mile Road and Van Dyke in Detroit at that time.

“Our police command center was the Herman Kiefer Hospital. We rode four officers in the patrol cars on 12 hour shifts,” he said. “We were shot at often and the department was very under armed at that time. Many of us carried our own weapons—I carried a Browning five-shot semi-automatic 12-gauge shotgun.”

Gage recalled a sniper at the Rialto Theatre in Detroit.

“We responded along with other officers to a sniper allegedly between the ‘R’ and ‘I’ in the marquee. The sniper would take shots at us or firefighters driving by. So they called it in and a few minutes later a Sherman tank from the National Guard came rolling down the street, aimed a 50 caliber machine gun at that sign, and all hell broke loose. No one ever climbed up there to see if they hit him.”

Gage recalled the looting of stores and apprehending suspects carrying away merchandise.

“They’d run out in the street holding a television or whatever and we’d have to grab them,” he said. “We’d have to hold on to them until the van came and took to the 10th Precinct on Livernois Avenue to the corral. It was hot and nasty those days of July. I’d go home at night and smelled like smoke, but at least I could go home every night, the Michigan State Police troopers did not. They stayed downtown on cots at the Detroit Armory.”

The 11th Precinct was then about 85 percent whites and only a small population of blacks, said Gage.

“I never saw the blacks mistreated in my five years of working downtown,” he said. “We arrested people, but it was for a reason. I walked the beat along 12th Street and before the riots it was a thriving business district. Every store was full. They all left between Davison and Warren Avenue after the riot. The blind pig where it all started was on the second floor of one of those buildings.”

Gage believes several factors sparked the unrest, including the construction of the Chrysler Freeway through traditional black neighborhoods on the east side in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

“Looking back it was a big insult to the black community when those roads were built,” he said. “There were plenty of jobs at the time, the auto plants were hiring people—they could not find enough workers. Unemployment was not a factor. Actually the unemployment is worse now.”

Gage remembered at the time of the riots, Detroit had 1.8 million people. Today the city’s population is about 672,000.

His experience in the Detroit Riots changed Gage.

“I was raised in a small town in the rural thumb of Michigan,” he said. “I had no interaction with minorities growing up. I learned that no matter if you’re black or white and you break the law, there are consequences. It’s not about race, but about focus on order. I never lost track that people are your boss—your actions have to withstand the front page of a newspaper. You have to be mindful of the public.”

“Over the years I’ve had drunks spit on me, curse at me and the next day they apologize. I just did my job.”

Gage returned to regular duty following the riots and later that year left Detroit for the Michigan State Police.

The violence escalated as both police and military battled to regain order in the city, and within 48 hours the National Guard was called to duty. According to news reports, 8,000 National Guard troops were called to help control the riots, including 25-year-old Norm Nowicki.

A Royal Oak resident and member of the Michigan Air National Guard 191st Tactical Reconnaissance group when the riots started, Nowicki was surprised by his call to duty.

“I was in my car when the news came over the radio to report to our base in Romulus,” said Nowicki, a Detroit native who moved to Brandon Township in 1972. “I reported to the base that night, perhaps 600-700 were in our group. I worked in food services. Basically, I was just a cook on the weekends and I reported to the base once a month, so I had never even fired a gun. They issued me and others a rifle, but told us not to load it. Many of us did load the weapons anyway. I thought to myself, ‘I’m not going to be target practice down there.’”

Nowicki, who also carried a 9 mm Luger as a sidearm, boarded a military bus and served a series of 16-hour stints near Monroe Street and I-75 in downtown Detroit during the riots.

“It was like a jungle down there,” he said. “We heard gun shots all the time and saw smoke from fires in the distance. Our job was to pull anyone suspicious over and search their car. It was just a bad situation. Still, other people were just glad to see us. Sometimes we would get sandwiches or drinks and thanks from residents.”

Nowicki also guarded some detained rioters that were housed in buses due to overcrowding at the city jails.

“The conditions were not the best for those people,” he said. “Just consider the weather was very hot and the only bathrooms were Port-a-potties, which required armed guards to walk the prisoners over to. Many just urinated right on the bus. The stench was unreal— it was so bad that police would just shove fire hoses in the bus and hand in bars of soap. It just made you sick.”

According to news reports, 4,700 paratroopers from the 82nd Airborne Division, ordered by President Lyndon B. Johnson were called in. In total, 33 African-Americans and 10 caucasians were killed, 1,189 people were injured, with more than 7,200 arrested.