And, now for the exciting conclusion — Part 2 of a two-part Don’t Rush Me column. If you missed Part 1, click HERE — Don

* * *

As I write, I’ve been sitting on this, mulling things over in my head for seven days. What would I write? How can I complete the circle on this branch of the Rush clan? Dad was a good egg, been gone since ‘96 and to tell Ma’s story, he has to be a part. Oh. If you haven’t heard Shirley Rush (Ma) passed away on August 31.

Her story needed to be more than her obituary. To those she met she was always a ray of sunlight. She offered genuine smiles. She had a way of taking in everything and returning something better. She was a soul of Grace and strength, something she has passed on to her three daughters, my younger sisters.

There’s not much I can write in this limited space that would do justice to her time on this spinning rock in the cosmos, but what the heck, let’s give it a whirl.

Like with us all, she was a product of her past. While Dad was a gregarious man — sentimentally wearing his emotions on his sleeve, Mom was the Ying to his Yang. She was thoughtful, measured. She consoled. She listened, she observed. She took life and whatever it was, she found a reason to smile.

She was fond of saying, “the sun always comes up tomorrow.”

It always amazed me how resilient and kind she really was. Some would have grown bitter and resentful had they lived her younger life. I often wonder how folks today would handle what life dealt her.

She was the first child of six kids her folks had. Grandma was 14 when she married Grandpa. Grandma was 15 when she had Ma, and 16 when they had Aunt Barb. The family moved up from the Appalachian side of the world to Michigan as migrant workers, picking cherries and living in canvas tents by the time Ma was three or four. Grandpa had a number of jobs before securing a gig with Great Lakes Shipping, where he helped construct barges like the Edmund Fitzgerald in the late 1940s. In the 1950s, Grandma and Grandpa had the rest of their brood, JoAnn, Jim, Janice and Jerry. They settled down in Detroit.

Ma enjoyed school. Did well. She made it all the way through the 10th grade, and part of 11th, when she was forced to quit and start working to take care of her sick parents and four youngest siblings. She got a good job working at Excello Corp in Detroit and actually did office work for late actor George C. Scott’s father. She worked, paid her family’s bills, saved money and traveled. Before Hawaii was a state, she went there. Five years after quitting high school she was planning a trip to Europe when she met a brash, dark-haired man with a twinkle in his brown eyes. A year later, they wed. Three years later, they started having kids.

Dad had his own demons, probably Post Traumatic Syndrome from time in Korea. Which is a nice, polite way to say, after a while he drank a lot. So, much so, when he died, I asked, “Why did you stay with Dad?”

To which she simply said, “He was the only one to make me feel young. He made me smile.”

She would have no other, even after he died. He was the light of her heart, and quite truthfully, she was his. I remember Dad telling me the story of my birth. I was a month late, Ma, all five foot nothing of her, was having issues. “Before you were born, the doctor said there’s a good chance one or both of them won’t make it through birth,” Dad recalled. “Sorry to say, son. I told the doctor, ‘make sure you save my wife.’ She was the best thing, aside from being your father, that has ever happened to me.”

* * *

Ma was kind, but she was also old-school tough. When I was a youngster I had a tendency to have loose lips — a polite way to say I would make glib remarks, even to the boys older than me. In the third grade, as I walked home I gave forth some pithy commentary to a group of three or four fifth grade boys, which they took umbrage to. I knew I was about to get the snot kicked out of me, so like a rabbit I bolted. It was only two blocks to the gate of our backyard and safety. I must have been quick, because I made it to the gate, past Ma, into the back yard and inside the house a goodly number of seconds before a cloud of dust and the boys arrived at the gate behind me.

I was safe!

As I watched from a window, the snarky smile on my face slowly melted. Outside Ma asked the mob what they wanted with her son, Donald. They were honest, told her what happened. And then she said. “Well, my son will fight you all. Not all at once though. One at a time. Donald, get out here.” And, the fun started. One at a time. Thanks, Ma.

That was when we lived in Redford Township. You know what? Her son learned nothing from that, and by the time we moved to Clarkston, my mouth still ran. And, so did I. In the seventh grade, I mouthed off to another bunch of kids, they gave chase, I ran. Mom intervened. I had to fight another bunch of kids, one at a time. Groovy.

In the five years I played football, she never watched a game. Didn’t like the violence. When I thought I lost my slot in college because I failed to hand in paperwork, she watched me punch the telephone pole outside our home. As she cleaned the blood from my hands, she simply said, “Call them. Figure it out.”

She wasn’t emotional. She didn’t do it for me. She calmly said, “Call them. Figure it out.”

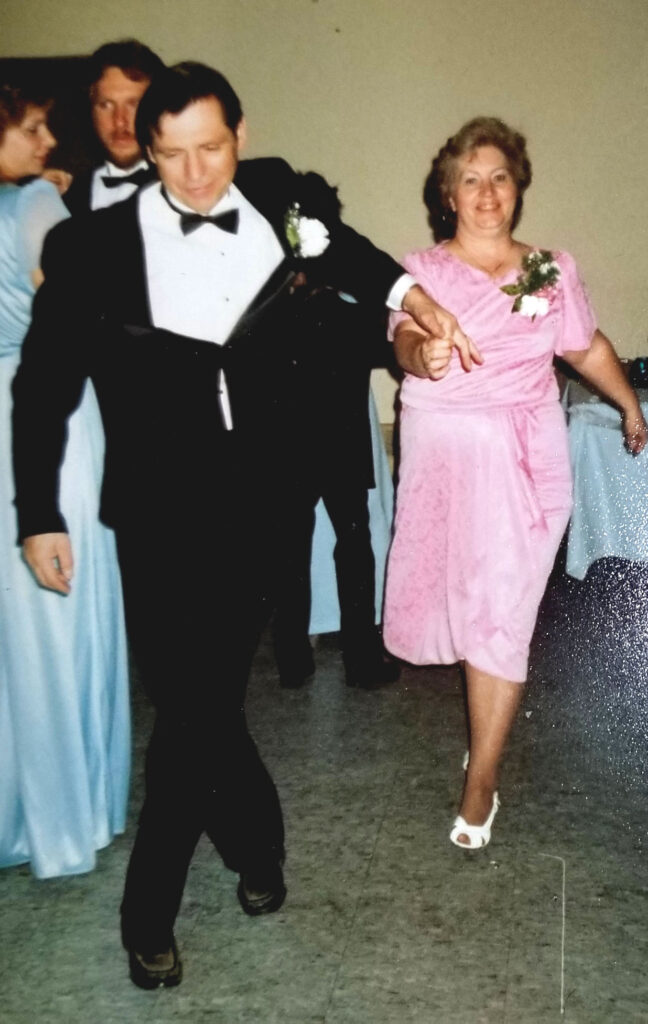

So, now she’s gone. It’s my hope — if I were to wish, well, upon two stars in the heavens at night — that together again, They dance. The circle’s complete.

RIP, Ma. Enjoy the view.